I co-owned a big, good-looking British motorcycle with a roommate in San Francisco in the early 1980s. We had a motorcycle club of two and it was fine that way, until an accident wrecked the bike and nearly killed me in April 1983. The machine was a 1972 Triumph T150 Trident, a big, heavy, triple-cylinder cruiser. It was fast and powerful, easy to handle in Triumph’s way, not too big and not small either. It had a giant black teardrop gas tank and long, flowing megaphone pipes, heavily chromed. My roommate nicknamed it “Freud.”

My roommates and I lived in a giant cheap flat on Valencia Street in the Mission District above the Lucca ravioli factory, and could get anywhere in the city quickly on that bike. Mostly it was for joyriding after work, barhopping, or heading out to Candlestick for a game – an exhilarating force of freedom and liberation.

Valencia at that time was a No Man’s Land, a busy north-south artery that formed a border between the heart of the low-rent Mission and the more affluent neighborhoods to the west. Valencia was wide, barren, no trees, windswept and gritty, literally. The 26 Valencia Muni bus spewed diesel particulate up and down the street, a black dusting you’d constantly wipe off your windowsills.

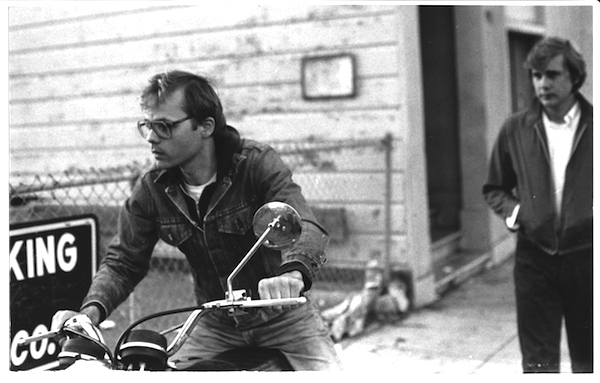

1981 Jan 1116 Valencia GMK aboard Freud.

About the same time the Triumph was wrecked – by a left-turn driver at 24th and Valencia who sent me to the hospital – some British motorcycle enthusiasts formed a loosely-organized riding club in San Francisco: the British Death Fleet. I learned about it from a woman who serviced the Xerox machines in the office where I worked in the Financial District. She rode a Limey with the BDF.

The name of the motorcycle club was derived ironically from the anti-British efforts of John Maher, the founder of the Delancey Street rehab organization. He was an Irish-American New Yorker who had come to San Francisco in the late 60s to kick a heroin habit – he converted his personal experience into a cold turkey/hard work program for addicts and ex-cons, and Delancey’s success made it an SF institution. The charismatic Maher became a civic force and politicians courted him for his influence. He was part of the strange brew of mid-70s San Francisco politics that included Jim Jones of the People’s Temple, who liberals could also count on to flood the neighborhoods with doorbell-ringing volunteers.

John Maher was a committed Irish nationalist. When the Royal Navy planned a goodwill visit to the Port of San Francisco in 1982 or 83, he launched a campaign to withhold SF’s famous hospitality from British tars. Feelings toward Brits in San Francisco’s Irish community in the early 80s were decidedly Anti after Margaret Thatcher, the Tory prime minister, had allowed Bobby Sands and other IRA hunger strikers to starve to death in Northern Ireland prison camps.

RIP Freud. Photo 1984 Gregory Kerwin

In San Francisco the Irish, many of them immigrants, ran the bars, from the best to the diviest. When the Royal Navy scheduled its port call, John Maher organized SF publicans to refuse service to their sailors. San Francisco loves sailors, this was a tough call, but Maher and the barkeeps made it. Maher’s campaign took the form of a crudely-drawn poster, a red skull superimposed over the Union Jack, that suddenly appeared in every neighborhood bar in San Francisco: No to the British Death Fleet!

I first saw the posters at the Dovre Club, a cheerless, linoleum-floored room on 18th Street between Valencia and Guerrero, run by a barman named Paddy Nolan. The Dovre is still around but at another location and without Paddy, who died in 1996. The Dovre had a legacy position in a corner of the Women’s Building, whose members didn’t want it there, and with whom Paddy had an active antagonistic relationship. I only drank there a few times and from my experience he had an antagonistic relationship with everybody else, too. San Francisco has its share of collectible curmudgeons, but Nolan was something else.

Naturally, Limey motorcycle-riders who were in love with their Triumph, as I was, or their BSA or Norton, immediately took up the poster as their banner – you’d see a group of five or six putting around San Francisco, British Death Fleet pinned to the back of their leather jackets. I never rode with them – but deeply appreciated the instant acquisition of the “brand.” You could find Maher’s faded posters hanging in the Dovre and other SF watering holes years after the Royal Navy’s visit.